This journey to better understand the relationships between key people, organizations and policies that make up our current mental health system has led me on a curious path. To this end I search and speak to key players, stakeholders and policymakers related to the topic of mental healthcare in Maricopa County. Every interview, phone call, literature search and discussion reveals a new perspective depending on which sector of the system the person comes from. I am discovering that when it comes to our current system, people that have been “in the game” for a long time have a deeper view of “the way we used to run things in the city” vs how we run the system today.

My work of better understanding the system has led to a logical starting point of developing a network system, or process map. It seems like a no brainer that before implementing an intervention in a system as large and complex as Maricopa County’s mental health system, that a first step would be to examine the current process flow. When I realized that this overall system mapping work has not been done in our county (or at least has not been published, or publicly shared) it seemed to be a clear starting point. Developing a simple map of the processes regarding the publicly funded crisis mental health system of Maricopa, is really actually not that simple at all.

When developing a network map one must first decide on the nodes (or actors) and the ties (or relationships) between the nodes in the network. For this work it is important to identify and label the actors in the system. I outline some of the important actors and relationships in the points below.

- After deinstitutionalization in the late 1970’s Arizona chose to distribute federal funds that were earmarked for state’s appropriation to administer a comprehensive community mental health system for ALL Arizonans by way of the Arizona State Department of Health (AZDHS).

- The historical timeline of Arizona’s mental health system was previously highlighted in my last blog post. Does it seem strange that from the historical milestone in 1981 until 2014 the timeline seems to have a huge gap? As I continue to explore the historical framework that built Arizona’s contemporary mental health “system” most avenues seem to land me at a pivotpoint in 1981- Arnold vs. Sarn court case.

- ADHS and Arizona State Hospital were sued in court case Arnold vs. Sarn. The decision which stated that “Arizona has failed to meet its moral and legal obligations to our state’s chronically mentally ill population”. The decision required a system delivery change to community-based programs and services for discharged patients.

- This is when the move from AZDHS as fiduciary of government appropriations for state mental health care moved to AHCCCS and then RHBA’s were developed.

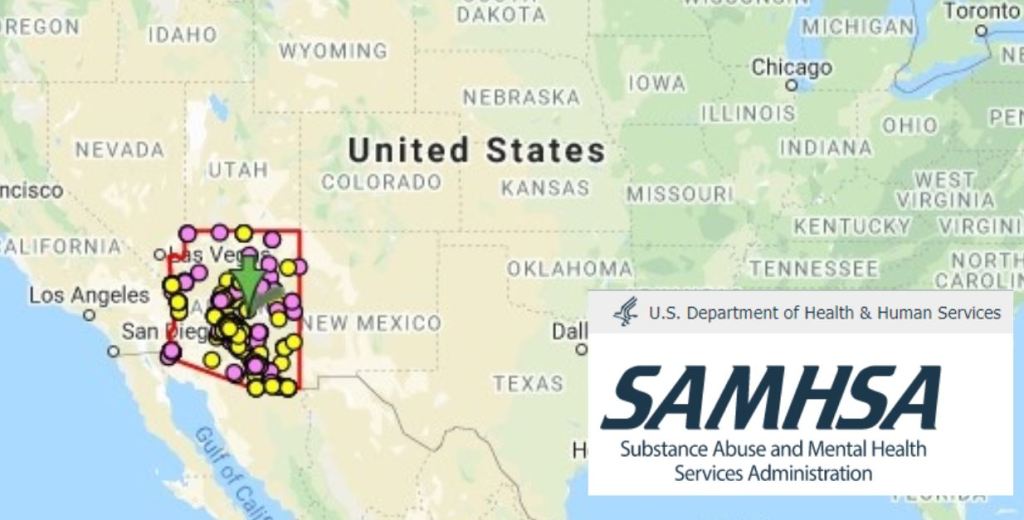

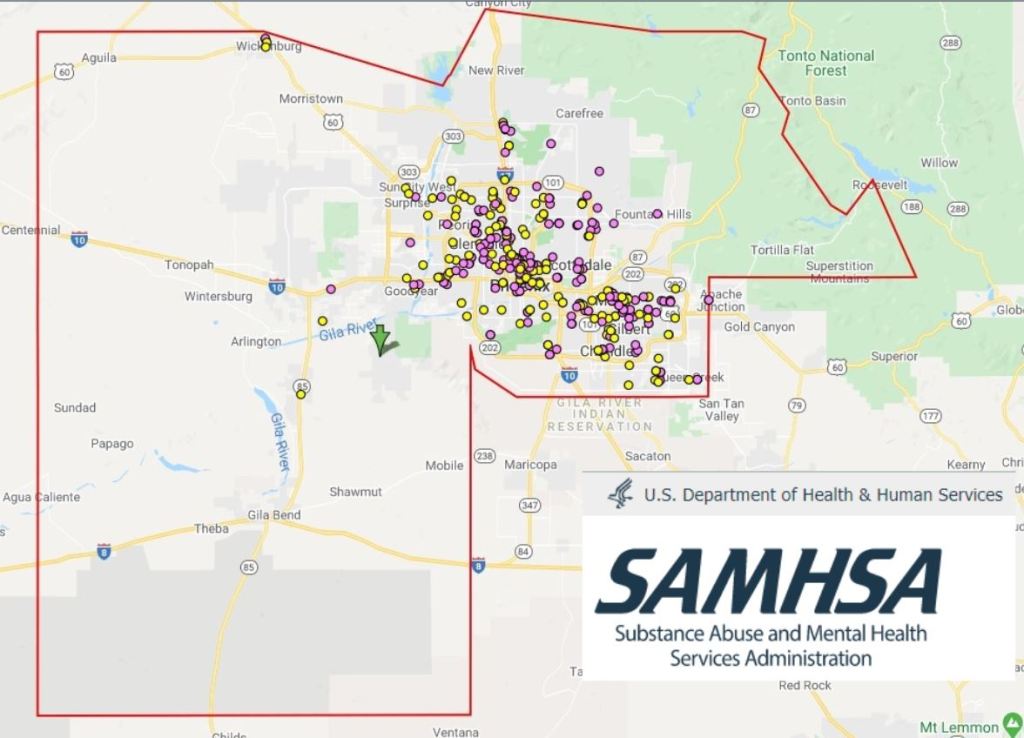

- In Arizona, the primary points of contact for SMI popluation fall under Regional Behavioral Health Authorities (RBHA), which serve the entire state.

- RBHA Regional Behavioral Health Authorities- (soon to be renamed the Regional Behavioural Health Administrators) are the contracted organizations who’s fiduciary responsibility is to provide comprehensive mental health services to Arizona’s SMI populations (in addition to other medicare recipients with chronic and acute mental illness). They are divided between three regions in Arizona (Northern, Central and Southern) and serve these regions through multiple networks of sub contracted providers, who then further contracted services to providers within their network.

- Private System: Hospitals, Emergency Rooms, Psychiatric Intake Facilities, Ambulance Companies

- Public Community Systems: First Responders (Police/Fire/ Crisis Response Teams/ Crisis Phone line)

- People- Arizona has estimated 41,511 people designated as “seriously mentally ill” (SMI) April 1, 2019

Seriously mentally ill persons are adults whose emotional or behavioral functioning is so impaired as to interfere with their capacity to remain in the community without supportive treatment. The mental impairment is severe and persistent and may result in a limitation of their functional capacities for primary activities of daily living, interpersonal relationships, homemaking, self-care, employment or recreation. The mental impairment may limit their ability to seek or receive local, state or federal assistance such as housing, medical and dental care, rehabilitation services, income assistance, or protective services.

Seriously emotionally disturbed are persons between birth and age 18 who currently or at any time during the past year have had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder that resulted in a functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits the person’s role or functioning in family, school, or community activities.

- Finally I circle back to Arnold vs. Sarn case that was settled in 2014 with requirements to provide key outcomes measured against national benchmarks for Arizona’s SMI population.

- In 2019 AHCCCS Service Capacity Assessment Report was published displaying the status of Arizona’s RHBA efforts to meet its fiduciary responsibility to uphold the agreement of the Arnold v Sarn case.

- Now in 2020, the structure of our mental health delivery system is changing again. Just a few days ago I attended a meeting hosted by AHCCCS, “The future of the RHBA”. has put out a request for proposals for a competitive contract expansion which will change the way care is delivered once again. The process is difficult to understand and seems to not be in the final stages. The meeting details some were decisions till not yet finalized. Below is a timeline for the planned changes.

- I have interviewed first responders (police and fire), social workers, case managers (I’m really growing a great dislike to that title ”case managers’ ‘). I have interviewed multiple key people serving at AHCCCS, and contracted provider networks. I have interviewed ambulance companies and doctors who work in our local ED. I have interviewed people who work in psychiatric intake facilities. Yesterday, I even got the honor of interviewing Mr. Chick Arnold! Yes, the Mr. Arnold vs. Sarn character! (More to come from this interview see the preview video below)

- There is a gap in my navigation of exploring this network of key players in our mental health system. I have focused a great deal on the delivery of care, and the policy that influences the delivery of care. However, I have not yet gained the perspective of the people for whom this system exists to serve. These people are the often missing perspectives from important decision tables in our system. It is my aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of ALL the key players in the system. This must include the ones who’s lives literally depend on the success of the mental health system, the ones most deeply vested–the patients. I have somehow regarded them as outsiders, and afterthoughts. What a big mistake.

Jade 16th and Buckeye 4/6/2020

Jade 16th and Buckeye 4/6/2020 with Chris at 27th ave &Bethany 4/5/2020

with Chris at 27th ave &Bethany 4/5/2020